May 25, 2017

To: Dr. Mandy Cohen, Secretary North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

On behalf of the North Carolina Association of Health Plans (NCAHP), we appreciate this opportunity to provide comments in response to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Service’s (DHHS’) request for comments on Medicaid transformation. We appreciate your efforts to carefully consider the input of the public and stakeholders in North Carolina’s Medicaid transformation and look forward to working with the Department and other stakeholders to ensure the successful implementation of sustainable, fiscally sound Medicaid reforms.

1. BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION

Background

The significant linkages between physical and behavioral health are well recognized; however, the systems designed to deliver services related to them have been maintained in independent and relatively uncoordinated systems. This is not unique to North Carolina, and there is broad recognition that these independent systems are not delivering the best outcomes for those that they serve. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “the solution lies in integrated care — the coordination of mental health, substance abuse, and primary care services. Integrated care produces the best outcomes and is the most effective approach to caring for people with complex health care needs.”

A lack of coordination and integration results in cost shifting across payers, “frequent flyers” in emergency departments, and unmet health care needs. Fragmented funding also makes it difficult to align performance incentives across the system.

In response, states increasingly are moving toward carving behavioral health services and populations into their Medicaid managed care programs, including most recently Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Nebraska, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Texas. System-level integration between physical and behavioral health allows providers and managed care programs to serve people, not conditions, and to address the bidirectional complexity between physical and behavioral health.

Recommendation | Work with the legislature to integrate behavioral health care services into Medicaid managed care contracts as soon as possible.

We strongly encourage North Carolina to consider system-level integration of physical and behavioral health services from the beginning of the State’s managed care program. Placing a single accountable pre-paid health plan (PHP) at risk for the total cost of care supports the highest level of whole-person care, the most effective value-based contracting across the entire delivery system, and streamlined care continuity for individual beneficiaries. Integration also reduces the Department’s administrative burden by reducing the number of entities it must oversee and avoids the confusion and frustration for beneficiaries that arises when they are forced to navigate disconnected provider networks.

Maintaining separate physical and behavioral health managed care programs for the first four years of managed care perpetuates unnecessary fragmentation, provider burden, poor health outcomes, and cost shifting.

Advantages to integrating behavioral and physical health include, but are not limited to the following:

- Members can build close relationships with a single care manager who has knowledge of their comorbidities and treatments across the entire continuum of care and can provide seamless access to needed services through a single network of providers.

- Using a single accountable entity for both the physical and behavioral health systems also allows for the customization of the clinical approach to appropriately align expertise based on the individual, for example using a behavioral health clinician or peer specialist for individuals with behavioral health needs.

- Financial incentives can be aligned across physical and behavioral health, encouraging investment in services that may be costly in one area, but lead to savings in another. For example, increased screening and treatment for depression in diabetic patients can lead to significant decreases in medical costs. Behavioral health issues are often a major driver of medical costs covered by the physical health benefit.

- PHPs become accountable for quality standards for both physical and behavioral health outcomes, encouraging health plans to focus on the whole person.

- Access to integrated, real-time data enables PHPs to implement targeted interventions and provide care coordination and transition support without administrative delays.

Recommendation | Ensure collaboration between stakeholders in developing standards for Special Needs Plans (SNPs).

It is our view that a single integrated system serving all members regardless of acuity level allows for better coordination of care. However, we understand that the Department may judge that Special Needs Plans (SNPs) are the preferred solution for populations with severe mental illness, intellectual/developmental disability (I/DD), and moderate to severe substance abuse disorder (SUD). Such large-scale changes require close collaboration between all system partners to prevent disruption for individuals and promote continuity of care. We encourage the Department to collaborate with providers, PHPs, and local management entities/managed care organizations (LME/MCOs) to jointly develop minimum requirements for SNPs and to set clearly defined criteria for which populations will be cared for by SNP plans.

Alternative Recommendations

We strongly support the full integration of behavioral health under the broader capitated managed care system; however, in its absence, we recommend strict coordination of care requirements for all contracted organizations. The State should build off of the existing infrastructure to enhance coordination with LME/MCOs. Further, it is important for the State to engage all stakeholders in ensuring continuity of care and transparency for North Carolina beneficiaries throughout the program transition, especially recognizing that many of the individuals currently served by the LMEs/MCOs have complex needs. It is extremely important for them, and for overall program success, to ensure that there are no gaps in care.

Recommendation | Adopt patient confidentiality rules no more stringent than federal law to facilitate information sharing.

It is important that the Department foster an ideal regulatory environment for information sharing between the physical and behavioral health management entities. Ideally, patient confidentiality rules would be no more stringent than federal law. Federal law provides very effective protections for patient privacy. Especially in programs where behavioral health is carved out, overly restrictive privacy laws prevent effective communication between managing entities, increasing fragmentation and hindering their collective ability to effectively manage the health needs of the member.

Recommendation | Require coordination between providers, including patient consents.

The Department should require network providers to participate in the integration of care effort by communicating about and coordinating care for shared patients, including obtaining patient consents necessary to inform and improve clinical decision-making.

Recommendation | Implement electronic health records.

The State should create effective electronic records and communication systems to allow providers to share information across the care team.

Recommendation | Encourage adoption of telehealth systems for behavioral health.

The Department should encourage the use of telehealth technology to expand access to behavioral health services, especially in rural areas.

2. PROVIDER TRANSFORMATION

Background

The most effective managed care programs minimize system complexity and administrative burden. We encourage the Department to establish operational standards and toolsets across all payers to simplify provider relationships with multiple payers (e.g., single credentialing process, common claims process).

In developing standards, the Department should weigh the benefits of reduced administrative burdens against the potential that they will inhibit innovation in care delivery, coordination, and payment models. Arbitrary targets or unnecessarily restrictive approaches are counter-productive to program goals. Standards should contain sufficient flexibility to ensure that program innovations and design features that “meet a provider where they are” are not hindered. Finally, it is critical that such standards allow both provider-led entities (PLEs) and traditional commercial managed care plans (CPs) to compete on a level playing field.

Finally, it is important to remember the close connection between the PHP capitation rates and provider reimbursement rates. Higher PHP capitation rates facilitate more-desirable PHP payment rates for providers, which generally encourages more providers to serve the Medicaid population. Adequate PHP capitation rates are especially important for North Carolina’s program, given the rate floor mandates included in the Medicaid transformation legislation. Sufficient rates also enable health plans to implement effective value-based payment models.

Recommendation | Centralize provider credentialing.

Provider credentialing is an administratively burdensome process for providers who contract with multiple health plans. The Department may consider centralizing the process by contracting with a single National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)-certified Credentialing Verification Organization (CVO).

Recommendation | Standardize other program elements.

Additional program elements that could be standardized include:

- Streamlined reporting – Require a standardized reporting system (e.g., through the State’s Health Information Exchange (HIE) and Informatics Layer) to simplify implementation and ensure consistent data.

- Standard provider education – Develop a standard program that educates providers about core components of the managed care model. We recommend that the Department and PHPs collaborate on provider trainings and communications to reduce duplication and to ensure that materials meet both provider and market needs.

- Streamlined quality measures – Consistent measures of quality will enable the Department and Medicaid beneficiaries to compare health plan performance.

Recommendation | Develop a centralized data infrastructure that supports the electronic exchange of clinical data.

Centralizing clinical data exchange through a health information exchange (HIE) and provider electronic health records (EHR) eases provider administrative burden while driving quality improvement and value by improving the collection and reporting of quality and performance data. The Department should coordinate closely with PHPs and providers in developing this system. A centralized system:

- Helps alleviate the burden on providers, who dedicate significant administrative resources to collecting and reporting clinical quality data for value-based payment and quality improvement initiatives.

- Lessens the burden on PHPs that must otherwise perform manual medical record chart reviews to collect data for quality reporting purposes.

- Allows data to flow between providers and PHPs to improve health outcomes, drive provider accountability, reduce unnecessary utilization, and lower costs.

Recommendation | Begin dialogue on encounter data recording and submission process early, working in collaboration with PHPs and providers.

Other states, such as New Jersey, have seen success by having all provider groups and PHPs at the table to discuss the process of collecting and submitting encounter data. This dialogue should begin six months to one year ahead of program implementation. This is particularly helpful for provider types that have never billed managed care before, as it provides an opportunity for technical assistance as well as open discussion with peers who already work with PHPs in other arenas.

Many rural providers are still submitting paper claims and will require a great deal of support to feel comfortable operating in the new Medicaid system. The Department should ensure that these providers receive appropriate training and technical support. Additionally, some states have eased the transition by accepting “imperfect” encounters submissions for the first 18 months. This would allow PHPs to start up, develop robust networks, ensure timely claims payment, and ensure that members receive services while the new system becomes fully operational.

Recommendation | Develop robust provider education programs.

We also encourage the Department to ensure adequate technical assistance is available to providers, particularly those newly transitioning to managed care. Other opportunities for provider technical assistance include the following:

- Program design and goals

- Contracting and credentialing processes

- Revenue cycle management, as providers shift from fee-for-service to value-based care

- Claims submission process for providers that have historically operated in a grant-based or other non-claims related environment

- Treatment and coordination of care for the “whole-person,” including behavioral health needs and Long Term Services and Supports (LTSS)

The Department should work closely with PHPs and providers during managed care program development to identify and address potential gaps in provider readiness to engage in managed care.

Recommendation | Consistent requirements across plan types.

The Department should apply insurance regulations and requirements consistently across all PHPs contracted to administer the State’s Medicaid managed care program under a fully capitated arrangement. Uniform application of requirements ensures equitable beneficiary protections and consistent quality of service across plan offerings. In particular, we recommend the Department hold provider-led entities (PLEs) to the same standards as traditional commercial managed care plans (CPs) in areas of beneficiary protection. For example:

- Adhering to requirements for member complaints and appeals

- Quality oversight

- Provider credentialing and licensure standards

- Network adequacy

- Value-based payment targets

Additionally, as risk-bearing entities, PLEs should be held to the same solvency requirements as risk-bearing or capitated CPs, commensurate with the number of Medicaid beneficiaries and amount of risk held by the entity. Requirements should include financial viability, minimum reserve requirements to cover claims costs, operating cash flow, capital and financial statement reviews. Participating full-risk organizations should be continuously monitored for financial health, and we encourage the Department to consider requiring stop-loss insurance to protect against catastrophic events that could dissolve an organization’s finances. Finally, we recommend that PLEs be held accountable for the same care coordination expectations of CPs and other risk-bearing entities. This ensures a minimum standard of quality and access for Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care and across all risk-bearing systems.

Other Suggestions

- Regular Meetings – We recommend that the Department hold regular meetings with PHPs and providers to address issues and concerns in a collaborative environment throughout the transition.

- Timely Access to Data – Provide PHPs and providers timely access to data and reports within the HIE and Informatics Layer (e.g., ensuring providers receive Daily Encounter Reports).

- Technology support – Small providers and providers in rural areas often do not have the resources or infrastructure to use technology. Additional attention should be paid to facilitating their integration into the managed care program’s information technology infrastructure. Some states have facilitated this infrastructure build by offering a small PMPM fee to providers to facilitate their development of electronic medical records and other infrastructure. A fee in the realm of $1 PMPM may be appropriate.

3. CARE MANAGEMENT AND POPULATION HEALTH

Background

North Carolina’s shift to Medicaid managed care and person-centered health communities requires the entire system to become more accountable for health outcomes and quality of care. It is important to note, however, that not every provider will be able (or want) to participate in this more-demanding environment of care coordination and accountability. Flexible PHP-provider partnerships will be critical to effectively accommodate the range of provider and community capabilities. Allowing unique strategies for clinical oversight, network development, value-based payment models, and other approaches to system level coordination will help ensure the success of the State’s Medicaid program.

Recommendation | Leverage value-based payment strategies to accomplish system-level integration and provide population health management support to providers.

Through the use of value-based payment (VBP) strategies, PHPs are able to provide targeted supports to providers based on their level of sophistication and ability to coordinate care across the broader system. These targeted supports assist providers in effectively managing care for Medicaid beneficiaries by addressing gaps in care that contribute to unmet needs or inappropriate utilization.

Recommendation | Allow flexible care management models developed collaboratively by PHPs and providers.

While it is important that North Carolina develop a consistent infrastructure across Medicaid providers, the Department should be cautious about mandating overly restrictive strategies for rural or small providers. Rather, the Department should allow flexibility for PHPs and providers to collaborate to tailor a support model that works best for a given provider

As North Carolina moves toward value-based payment, it will be important to remember that value-based clinical management represents a culture change for providers accustomed to rendering care in a fee-for-service environment, and it will be difficult for many of these providers to manage risk. Thus, we reiterate the role that contracted PHPs can play in supporting a new delivery system. There is a broad range of value-based methods that PHPs can bring to providers based on their readiness to participate in the new system, and it will be important that North Carolina not be overly prescriptive as to how these PHP-provider relationships develop, but rather let PHPs and providers develop strategic partnerships that are based on mutual goals and aligned with the State’s overarching system transformation goals.

Recommendation | Avoid mandating specific relationships between PHPs and providers or other organizations.

The Department should not mandate specific partnerships between PHPs and providers or community-based organizations. The Department should include sufficient flexibility in its program design to allow these stakeholders to develop strategic partnerships that align with the goals of the broader managed care program and that accommodate provider sophistication and readiness. This extends to the types of services that are best managed at a local or provider level versus those best managed at an PHP level; PHPs and providers should have flexibility in their contractual relationships to determine responsibility and accountability based on the provider’s experiences and ability to bear risk.

Similarly, we encourage the Department not to mandate an enhanced care management fee, but rather allow this approach as one of multiple strategies that PHPs can leverage based on the preferences of a given provider practice. A flexible approach also ensures that the maximum number of providers are able to participate in advanced clinical and payment models informed by patient panels, regional variation, and practice preparedness to evolve.

4. ADDRESSING SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Background

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are a critical factor in health outcomes. Social services are typically spread across numerous agencies within a state, each with distinct financing and leadership as well as varying degrees of data infrastructure and capabilities. This fragmentation makes it difficult to coordinate access to the services to address a person’s full needs. These coordination challenges are exacerbated when an individual’s health care needs are served by multiple state programs, resulting in considerable fragmentation and unmet needs.

Recommendation | Streamline financing, data, infrastructure, and administration to the extent possible across both social services and the State’s Medicaid managed care program(s).

To foster integration and coordination across health care and social service programs, we encourage North Carolina to streamline financing, data, infrastructure, and administration to the extent possible across both social services and the State’s Medicaid managed care program(s). We recommend that the Department:

- Consider identifying a single program administrator tasked with coordinating health and social support programs to ensure a cohesive leadership philosophy, mitigate competing priorities across programs, reduce burdens, and provide technical assistance for providers, communities, and PHPs.

- Pilot program models that streamline financing across health care and social services. For example, one potential model could provide a pooled/single payment that includes health and social services funding to PHPs with the Department managing the inter-agency collaboration to braid the funding on the backend. This approach prevents cost shifting across services, promotes program sustainability, reduces administrative burdens, affords synergies across the various partners, ensures care continuity, and improves patient experiences. When effectively designed, it also allows for all agencies to share in the system savings achieved through the holistic management of health and social services and offers opportunities for re-investment if programs are successful in achieving cost savings.

- Improve SDOH data accessibility to enable program coordination and linkages across an individual’s whole experience. SDOH data is often unavailable or unlinkable to health care data due to variable eligibility pathways, program resources, data infrastructure, and data collection methods. Targeting state resources to bring consistency to data collection and storage methods across social service programs (e.g., through a common population health platform), and ensuring that appropriate data is collected will create opportunities to identify needed interventions and use predictive analytics to target limited resources to individuals based on combined need.

- Improve medical coding of SDOH through health care provider education. The current ICD-10 medical coding system includes V-codes that allow providers to denote specific social issues, such as homelessness. More accurate coding of these issues within the health care system will allow the Department and PHPs to better understand population needs and implement targeted solutions.

Recommendation | Minimize program carve-outs.

As the Department contemplates strategies to increase coordination across health care and social services programs, it will be important to limit program “carve-outs” from its Medicaid managed care program. Carve-outs add unnecessary layers of fragmentation to an individual’s care and create benefit cliffs for individuals who move across eligibility categories (e.g., individuals who must become “severe” enough to qualify for services that are necessary to prevent that same degree of severity). While the ideal program would fully integrate all populations and services under a single group of PHPs, we recognize that this approach would require legislative change that could delay North Carolina’s ability to implement managed care.

Thus, to afford the State, its providers, and Medicaid recipients the benefits of managed care within the current proposed timeframe, we recommend that the Department consider implementing the program as proposed in its waiver, but with the goal of eliminating population and service carve-outs as soon as possible to provide individuals with behavioral health needs, those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and the I/DD population with fully integrated managed care. Such an approach would allow the Department to work through legislative changes and waiver revisions during the 18 months preceding program implementation, with the ultimate goal to create a program that addresses the whole person, including their physical, behavioral, LTSS, and social services needs.

Recommendation | Assess needs, availability, and utilization of current support programs among Medicaid beneficiaries.

Available SDOH data in North Carolina suggest that food insecurity is one of the most significant vulnerabilities for state residents. This is just one of many socioeconomic factors that are likely creating barriers for North Carolina’s Medicaid beneficiaries.

Dramatically increasing referrals to social services, which can happen during the transition to managed care, stresses an already resource-constrained support system, and anticipated limitations will need to be considered prior to implementation. In order to effectively inform the State’s transition efforts, we recommend the Department first assess the needs of the Medicaid population within the context of existing benefit allocation to determine where appropriate investments and coordination are needed. For example, North Carolina might find that some services are available but underused, suggesting that system navigation support and community health workforce would be important investments. Additionally, we encourage the Department to consider any potential program design elements that might impact SDOH, such as work requirements that might require investment in employment supports and work training.

Recommendation | Add housing and employment support to the fee schedule.

The Department should consider adding housing and employment support services to the fee schedule so that formal services can be provided to beneficiaries who need them. The Department should also partner with housing and vocational programs.

5. IMPROVING QUALITY OF CARE

Background

North Carolina is taking an important step toward increasing the level of quality in its Medicaid program through its focus on value-based care and increased accountability. As the Department implements these programs, it will be essential to ensure appropriate incentives and metrics are in place to reward increased quality while simultaneously not overburdening providers and other stakeholders with administrative reporting that can accompany such programs.

Recommendation | Adopt widely used quality metrics.

The Department should adopt a quality framework based on commonly used quality measures. The Department may consider metrics such as the Medicaid Adult and Child Core Measures and/or NCQA Medicaid Accreditation Measures, which include HEDIS. The Accreditation and Medicaid Core Measure sets address critical aspects of the delivery system that touch the broad Medicaid population, including prevention, clinical management, and health plan efficiency and management. As the Accreditation and Core Measures are widely used in Medicaid programs today, their adoption as a part of a broader framework should be smooth. Additionally, the holistic nature of these measure sets will help North Carolina reduce overlap and administrative inefficiency in the collection and reporting of data among both managed care plans and providers.

Recommendation | Phase in quality measures over time.

During the first year of the program, we encourage the Department to focus on process measures that support successful program implementation. After the first year, the Department should implement an incentive model in managed care contracts that rewards quality measures that align with the program’s Quality Improvement Strategy as well as the spirit and goals of the CMS Final Rule on Medicaid managed care (CMS-2390-F). The most effective health plan incentive models specify, at the beginning of each contract year, target scores and dollar/percentage amounts of associated awards (or penalties). Models of this type use health plan performance in the prior contract year as the measurement baseline, unlike other models, which use other past performance or estimates for future performance. Models that use this retrospective comparison approach allow health plans to proactively evaluate their own performance and work toward continuous improvement throughout the contract year.

Recommendation | Develop efficient but flexible quality standards and reporting.

The Department should leverage the PHP-provider relationships established through value-based payment methods to support providers in quality improvement efforts and to reward them for high-quality care. In managed care programs, PHPs are best positioned to provide incentives and tailored feedback to providers based on the provider’s experience, sophistication, infrastructure, and ability to bear risk. PHPs are also able to work with high-performing providers to reduce administrative burdens (such as prior authorization requirements), providing the flexibility these providers need to continue improving.

Currently, both providers and health plans are required to report results on a myriad of quality-focused programs, often with disparate metrics and reporting tools. The Department should use its Quality Improvement Strategy to create administrative and reporting efficiencies for health plans and providers. Additionally, to increase transparency to members, the Department’s Quality Improvement Strategy should evaluate outcomes at the point-of-care and assess whether plans are contracting with the providers that achieve the best patient outcomes.

6. PAYING FOR VALUE

Background

North Carolina’s Medicaid program has a tremendous opportunity to encourage the adoption of value-based payment (VBP) models and to advance delivery system and payment reform. We strongly support the adoption of value-based arrangements.

Recommendation | Benchmarks for VBP should account for appropriateness of value-based arrangements for various types of providers and provider-readiness.

As the Department develops benchmarks or targets for value-based purchasing, it should consider the range of different types of providers and provider-readiness to ensure that metrics are not skewed by provider contracts in which VBP arrangements would not be appropriate. For example, value-based arrangements for primary care physicians should obviously be encouraged. However, for contracts with a manufacturer of wheelchair ramps, VBPs don’t make sense. Benchmarks should take this into account.

Recommendation | Establish bonus program.

The most effective way to encourage value-based purchasing arrangements is to establish state goals and reward Medicaid managed care plans that meet these goals.

- States have been most effective at encouraging the use of VBP by offering of a set of bonus payments to PHPs that meet or exceed benchmarks on five to ten state-established quality metrics. States operating this structure often offer health plans a bonus for improving selected metrics compared to the previous year, as well as a separate bonus for performing well compared to other health plans.

- A system of bonus payments for performance is preferable to a withhold model. Withholding a portion of health plans’ capitations payments, to be paid only if quality metrics are met, may be less productive to a state’s interest in promoting VBP. A withhold model restricts the funding Medicaid managed care plans have access to throughout the year, limiting their ability to put value-based purchasing principles into place and engage providers in VBP contracts that offer performance bonuses.

- A bonus model also allows PHPs to access their full capitation amount throughout the year and to push additional funds to providers through VBP arrangements that support state quality goals.

Recommendation | Consider adopting the Learning & Action Network alternative payment model framework.

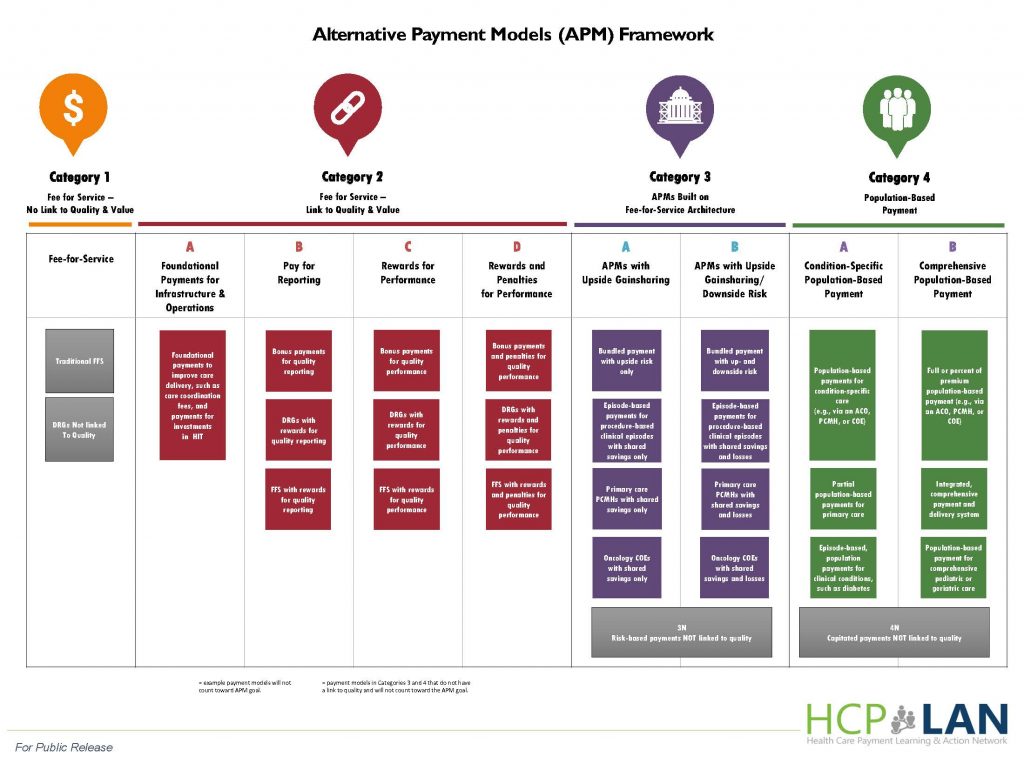

One option the Department may consider for encouraging value-based purchasing could be setting yearly requirements that a certain percentage of PHP medical revenue utilize value-based payment arrangements in each alternative payment model (APM) category, as defined by the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (LAN).

The program should ease into value-based payment requirements by mandating increasing use of value-based structures over the course of the first few program years. For example, the Department may allow Categories 1 through 3 of the LAN framework to qualify as value based arrangements initially. Then, over the next few years, the Department could transition to allowing only Categories 3 and 4 to qualify.

7. ACCESS AND TREATMENT FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

The State should educate prescribers of opiates about member tolerance, dependence, and addiction. This should be required continuing medical education.

Recommendation | Prescription monitoring program.

The State should consider a mandatory drug monitoring program that prescribers must check before writing a prescription. The program should include:

- Both insurance- and cash-paid prescriptions.

- Pharmacies in other, especially neighboring, states if possible.

Recommendation | Pharmacy lock-in program

We recommend that the State utilize a pharmacy lock-in program for members with inappropriate or excessive drug utilization histories.

Other recommendations:

- The State should encourage the utilization of Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT).

- The State should offer a full continuum of SUD services per American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM) standards.

- The State should engage in community education around tolerance, dependence and addiction

- The State should engage in community education to reduce the stigma of SUD, especially opiate addiction.